Joan of Arc

Chapter 3

THE CORONATION AT RHEIMS

Leaving the now free and happy town to jubilate in its deliverance

from the enemy, Joan of Arc went by Blois and Tours to Chinon. At

Tours the King had come to meet the Maid. When within sight of the

King, Joan dismounted and knelt before him. Charles came forward

bareheaded to meet her, and embraced her on the cheek; and, to use the

words of the chronicler, made her 'grande chère'. It was on this

occasion that the King bestowed on Joan of Arc the badge of the Royal

Lily of France to place in her coat-of-arms. The cognizance consisted

of a sword supporting a royal crown, with the fleur-de-lis on either

side.

Joan now strongly urged the King to lose no time, but at once go to

Rheims, to be crowned. The fact of his being crowned and proclaimed

King of France would add infinitely to his prestige and authority; he

would then no longer be a mere Dauphin or King of Bourges, as the

English and Burgundians styled him. But now Joan found how many at

Court were lukewarm. The council summoned to deliberate on her

proposal alleged that the King's powers and purse would not enable

him to make so long and hazardous an expedition. Joan used every

argument in favour of setting out forthwith for Rheims: she declared

that the time given to her for carrying out her mission was short,

and, according to the Duke of Alençon's testimony, she said that after

the King was crowned she would deliver the Duke of Orleans from his

captivity in England, but that she had only one year in which to

accomplish this task; and therefore she prayed that there might be no

delay in starting for Rheims.

Charles was now staying at the Castle of Loches, that gloomy

prison-fortress whose dungeons were to become so terribly notorious in

the succeeding reign. Joan, whose impatience for action carried her

beyond the etiquette of the Court, entered on one occasion into the

King's private apartment, where the feeble and irresolute monarch was

consulting with his confessor the Bishop of Castres, Christophe

d'Harcourt, and Robert de Maçon. Kneeling, the Maid said:—

'Noble Dauphin, hold not such long and so many councils, but start at

once for Rheims, and there receive your crown.'

'Do your voices inspire this advice?' asked the King's confessor.

'Yes,' was the answer, 'and with vehemence.'

'Then,' said the Bishop, 'will you not tell us in the King's presence

in what way your voices communicate with you?'

To this Jesuitical query, Joan, in her simple and straightforward

manner, answered the priest, that when she met with people who doubted

the truth of her mission she would retire to her room and pray, and

then voices returned and spoke to her:—'Go forward, daughter of God,

and we will assist you,' and how hearing those voices and those words

she would rejoice and take courage, and only long that her then state

of happiness might last always. While telling them these things she

seemed a being transformed, surrounded by a something Divine and holy.

It was not unnatural that the King and his councillors should hesitate

before making up their minds to undertake the journey to Rheims, for

the English were posted in force at Beaugency, at Meun, where Talbot

was encamped, and at Jargeau. They also held a strong position on the

Loire; it would be difficult to reach Rheims without encountering some

of their forces. Jargeau had been attacked, indeed, by Dunois and

Xaintrailles, but unsuccessfully; and there was real danger in going

northwards while the English were still so plentiful and so strongly

entrenched in the towns of the centre and south of France. Another

reason for delaying the journey to Rheims and the ceremony of the

coronation, was that some time must elapse before the princes and

great nobles, who would have to take part in the coronation, could

assemble at Rheims.

Joan, thus thwarted in her wish of marching directly on to Rheims,

suggested driving the English from their fortresses and encampments

on the Loire. To this scheme the royal consent was obtained, and the

Duke of Alençon was placed in command of a small force of soldiers.

Joan directed the expedition, and it was ordered that nothing should

be done without the sanction of the Maid.

In a letter, dated the 8th June, 1429, written by the young Count of

Laval, who met Joan of Arc in Selles in Berri, the place of rendezvous

for the expedition, is a pleasant notice of the impression the heroine

caused him. He describes her as being completely armed, except that

her head was bare. She entertained the Count and his brother at

Selles. 'She ordered some wine,' he writes, 'and told me that I should

soon drink wine with her in Paris.' He adds that it was marvellous to

see and hear her. He also describes her leaving Selles that same

evening for Romorantin, with a portion of her troops. 'We saw her,' he

writes, 'clothed all in white armour excepting her head; her charger,

a great black one, plunged and reared at the door of her lodging, so

that she could not mount him. Then she said, "Lead him to the Cross,"

which cross stood in front of the church on the high road. And then he

stood quite still before the cross, and she mounted him; then as she

was riding away she turned her face to the people who were standing

near the door of the church; in her clear woman's voice she

said:—"You priests and clergy, make processions, and pray to God for

our success." Then she gave the word to advance, and with her banner

borne by a handsome page, and with her little battle-axe in her hand,

she rode away.'

The church before which this scene took place at Selles-sur-Cher still

exists, a fine massive building, dating from between the eleventh and

thirteenth centuries; but the old cross that stood before it, to which

Joan of Arc's black charger was led, has long ago disappeared.

In my opinion, this graphic description of the Maid of Orleans,

written by Guy de Laval to his parents, is the best that has come down

to our day of the heroine. There is to us a freshness about it which

proves how deeply the writer must have been stirred by that wonderful

character; it shows too that, with all her intensely religious and

mystic temperament, Joan of Arc had a good part of sprightliness and

bonhomie in her character, which endeared her to those whose good

fortune it was to meet her.

The incident of the black charger standing so still beside the cross,

and the figure of the Maid, mystic, wonderful, in her white panoply,

with her head bare—that head which, in spite of no authentic portrait

having come down to us, we cannot but imagine a grand and noble

one—make up a living picture of historic truth, far above the fancies

evolved out of the brains of any writer of fiction—for is it not

romance realised?

The eagerness to accompany Joan of Arc in this expedition of the Loire

was great. The Duke of Alençon wrote to his mother to sell his lands

in order that money might be raised for the army. The King was unable

or unwilling to pay out of his coffers the expenses of the campaign.

From all sides came officers and men eager for new victories under the

banner of the Maid.

Joan led the vanguard, followed by Alençon, de Rais, Dunois, and

Gaucourt. At Orleans they were joined by fresh forces under Vendôme

and Boussac. On the 11th of June the army amounted to eight thousand

men. Jargeau was the first place to be attacked. Here Suffolk, with

between six and seven thousand men, all picked soldiers, had

established himself. Inferior in numbers, the English had the

advantage over the French in their artillery. In the meanwhile,

Bedford, who had news of Suffolk's peril, sent Fastolfe to Jargeau,

with a fresh force of five thousand men. But for some reason or other

Fastolfe seemed in no hurry to come to Suffolk's assistance; he lost

four days at Etampes, and four more at Jauville. Some alarm seems to

have been felt among the French troops at the news of Fastolfe's

approach. Joan mildly rebuked those who showed anxiety by saying to

them: 'Were I not sure of success, I would prefer to keep sheep than

to endure these perils.'

The faubourgs of the town of Jargeau were attacked and taken, but

before storming the place, Joan, according to her habit, sent a

summons to the army. She bade the enemy surrender: doing so, he would

be spared, and allowed to depart with his side-arms; if he refused,

the assault should be made at once. The English demanded an armistice

of fifteen days: hardly a reasonable request when it is remembered

that Fastolfe, with his reinforcements, might any day arrive before

Jargeau. Joan said they might leave, taking their horses with them,

but within the hour. To this the English would not consent, and it was

decided to attack upon the following morning.

The next day was a Tuesday; the signal was given at nine in the

morning. Joan had the trumpets sounded, and led on the attacking

column in person. Alençon appears to have thought the hour somewhat

early; but Joan overruled him by telling him that it was the Divine

will that the engagement should then take place. 'Travaillez,' she

repeated, 'Travaillez! et Dieu travaillera!'

These words may well be called Joan of Arc's life motto, and the

secret of her success. 'Had she,' she asked Alençon, 'ever given him

reason to doubt her word?' And she reminded him how she had promised

his wife to bring him, Alençon, back safe and sound from this

expedition. Joan seems throughout that day's fighting to have watched

over the Duke's safety with much anxious care; at one hour of the day

she bade him leave a position from which he was watching the attack,

as she told him that if he remained longer in that place he would get

slain from some catapult or engine, to which she pointed on the walls.

Hardly had the Duke left the spot when a Seigneur de Lude was struck

and killed by a shot from the very engine about which Joan had warned

Alençon.

Hour after hour raged the attack; both Joan and Alençon directed the

storming parties under a heavy fire. A stone from a catapult struck

Joan on her helmet as she was in the act of mounting a ladder—she

fell back, stunned, into the ditch, but soon revived, and rising, with

her undaunted courage, she turned to hearten her followers, declaring

that the victory would be theirs. In a few more moments the place was

in possession of the French. Suffolk fled to the bridge which spanned

the Loire: there he was captured. A soldier named William Regnault

beat him to the ground, but Suffolk refused to yield to one so low in

rank, and is said to have dubbed his victor knight before giving him

up his sword. Besides Suffolk, a brother of his was taken, and four or

five hundred men were killed or captured. The place was pillaged. The

most important of the prisoners were shipped to Orleans.

The following day Joan returned to Orleans with Alençon, where they

remained two days to rest their men, after which they proceeded to

Meun. This was a strongly fortified town on the Loire, about an equal

distance from Orleans on the west and from Jargeau on the east.

The first success of the French was the occupation of a bridge held by

the English. They then descended the river, and attacked the town of

Beaugency. This town had been abandoned by the English garrison, who

had thrown themselves into the castle. Here it was that the army of

the Loire was joined by the Constable de Richemont, who could be

almost considered as a little monarch in his own territory of

Brittany. This magnate appears to have been a somewhat unwelcome

addition to Joan and Alençon's army. He was, however, tolerated, if

not welcomed. Alençon and the Constable, who had till now been at

enmity, were reconciled by Joan's influence, and she paved the way for

a reconciliation between Richemont and the King.

It was high time that all the French princes should be reconciled, for

the danger from the invaders was still great even in the immediate

circle of the Court and army. A strong body of men was known to be on

the way from Paris, under the command of Fastolfe, and Talbot was

marching to meet him with a force from the Loire district; they soon

met, and together proceeded directly upon Orleans. Fastolfe appears to

have been disinclined to attack, his force being smaller than that of

the French; but Talbot was beside himself with rage at having to

retreat from Orleans, and swore by God and St. George that, even had

he to fight the enemy alone, fight he would. Fastolfe had to give way

to the fiery lord, although he told his commander that they had but a

handful of men compared to the French; and that if they were beaten,

all that King Henry V. had won in France with so much loss of life

would be again lost to the English.

Leaving some troops to watch the English garrisons in the castle of

Beaugency, Joan marched against the English. The hostile armies met

some two miles between Beaugency and Meun. The English had taken up a

place of vantage on the brow of a hill; their archers as usual were

placed in the front line, and before them bristled a stockade. The

French force numbered about six thousand, led by Joan of Arc, the Duke

of Alençon, Dunois, Lafayette, La Hire, Xaintrailles, and other

officers.

It was late in the day when heralds from the English lines arrived

with a defiant message for the French. Joan's answer was firm and

dignified. 'Go,' she said to the heralds, 'and tell your chiefs that

it is too late for us to meet to-night, but to-morrow, please God and

our Lady, we shall come to close quarters.'

The English were still strongly fortified in the little town of Meun.

A portion of their army left Beaugency in order to effect a junction

with their other comrades, and in perfect order Talbot commenced his

retreat on Paris, taking the northern road through the wooded land of

La Beauce. They were closely followed by the French, but neither army

had any idea how near they were to one another till a stag, startled

by the approach of the French, crossed the English advanced guard. The

shouts of the English soldiers on seeing the stag gallop by was the

first sign the French had of the propinquity of their foes. A hasty

council of war was held by the French commanders. Some were for delay

and postponing the attack until all their forces should be united; and

these, the more prudent, pointed out the inferiority of their force to

that of the enemy, arguing that a battle under the circumstances, in

the open country, would be hazardous. Joan of Arc, however, would not

listen to these monitions. 'Even,' she cried, 'if they reach up to the

clouds we must fight them!' And she prophesied a complete victory.

Although, as ever, anxious to command the attack, she allowed La Hire

to lead the van. His orders were to prevent the enemy advancing, and

to keep him on the defensive till the entire French force could reach

the ground. La Hire's attack proved so impetuous that the English

rearguard broke and fled back in confusion. Talbot, who had not had

time, so sudden and unexpected had been the French attack, to place

his archers and defend the ground, as was his wont, with palisades and

stockades, turned on the enemy like a lion at bay. Fastolfe now came

up to Talbot's succour; but his men were met by the rout of the

rearguard of the broken battle, and the fugitives caused a panic among

the new-comers. In vain did Sir John attempt to rally his men and face

the enemy. After a hopeless struggle, he too was borne off by the tide

of fugitives. One of these, an officer named Waverin, states the

English loss that day to have amounted to two thousand slain and two

hundred taken, but Dunois gives a higher figure, and places the

English killed at four thousand.

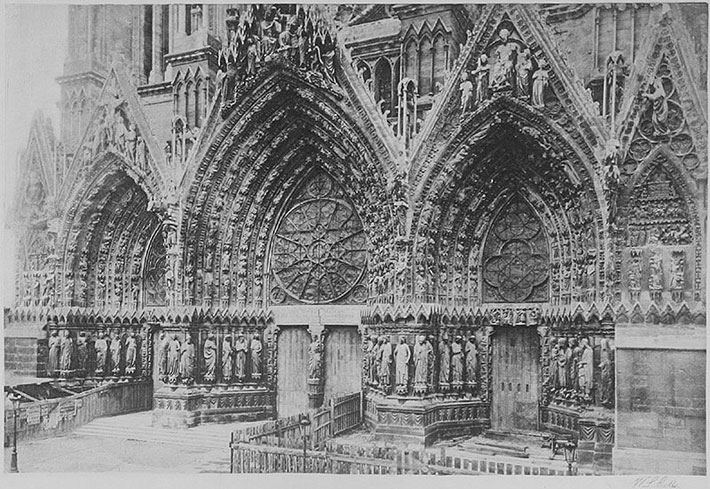

WEST PORTAL - RHEIMS

WEST PORTAL - RHEIMS

This battle of Patay was the most complete defeat that the English had

met with during the whole length of that war of a hundred years

between France and England; and, to add to its completeness, the

hitherto undefeated Talbot was himself amongst the taken.

'You little thought,' said Alençon to him, when brought before him,

'that this would have happened to you!'

''Tis the fortune of war,' was the old hero's laconic answer.

The effects of this victory of Patay on the fortunes of the English in

France were greater than the deliverance of Orleans, and far more

disastrous, for the French had now for the first time beaten in the

open field their former victors. The once invincible were now the

vanquished, and the great names of Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt had

lost their glamour. When the news was known that the English under

Talbot and Fastolfe had been beaten, and that the great commander for

so many years the terror of France had been made a prisoner, and that

these mighty deeds had been accomplished by the advanced guard of the

French army under the inspiration of the Maid of Orleans, the whole

country felt that the knell of doom of the English occupation in

France had rung.

There is an anecdote relating to Joan of Arc at Patay that should find

a place here. After the battle, and while the prisoners were being

marched off by the French, Joan was distressed to see the brutality

with which those captives unable to pay a ransom were treated. One

poor fellow she saw mortally wounded by his captors. Flinging herself

from her saddle, she knelt by the side of the dying man, and, having

sent for a priest to shrive him, she remained by the poor fellow's

side and attended to him to the end, and by her tender ministrations

helped him to pass more gently over the dark valley of death.

Michelet discovered this story in the deposition of Joan of Arc's

page, Louis de Contes, who was probably an eye-witness of the scene.

With this brilliant victory at Patay closed Joan of Arc's short but

glorious campaign on the Loire. Briefly, this was the career of her

victories:—On the 11th of June the Maid attacked Jargeau, which

surrendered the next day. On the 13th she re-entered Orleans, where

she rallied her troops. On the 15th she occupied the bridge at Meun,

and the following day she attacked Beaugency, which yielded on the day

after. The English had in vain hoped to relieve Jargeau: they arrived

too late. After the fall of Beaugency they fell back, and were

defeated at Patay on the 18th.

A wonderful week's work was this campaign, ordered and led by a maiden

of eighteen. What made Joan of Arc's success more remarkable is the

fact that among the officers who served under her many were lukewarm

and repeatedly foiled her wishes. And it is not difficult to trace the

feeling of jealousy that existed among her officers; for here was one

not knight or noble, not prince, or even soldier, but a village

maiden, who had succeeded in a few days in turning the whole tide of

a war, which had lasted with disastrous effects for several

generations, into a succession of national victories. This

professional jealousy, as one may call it, among the French military

leaders was fomented and aggravated by the perfidious counsellors

about the King. The only class who thoroughly appreciated and were

really worthy of the Maid and her mission, were the people. And it is

still by the people that everlasting gratitude and love of the heroic

Maid are most deeply felt.

While Joan was gaining a succession of victories on the Loire, the

indolent King was on a visit to La Tremoïlle at his castle of

Sully-sur-Loire. Accompanied by Alençon and the Constable Richemont,

Joan repaired to Sully. She had promised to make the peace between

Charles and Richemont, and as the Constable had brought with him from

his lands in Brittany fifteen hundred men as a peace-offering, the

reconciliation was not a matter of much difficulty. La Tremoïlle saw

with an evil feeling the ever-growing popularity of Joan, and feared

her daily increasing influence with the King; but he could not prevent

the march on Rheims, much as he probably wished to do so. It was

arranged that the army should be concentrated at Gien. From Gien, Joan

addressed a letter to the citizens of Tournay, a town of doubtful

loyalty to Charles, and much under the influence of the Burgundian

party. She summoned in this letter those who were loyal to Charles to

attend the King's forthcoming coronation.

On the 28th of June the King and Court left Gien, on their northern

march. That march was not a simple matter, for a country had to be

traversed in which the towns and castles still bristled with English

garrisons, or with doubtful allies. Auxerre belonged to the Burgundian

party, always in alliance with the English; Troyes was garrisoned with

a mixed force of English and Burgundians; and the strongly fortified

places on the Loire, such as Marchenois, Cosne, and La Charité, were

still held by the English troops. Charles' army had no artillery; it

was therefore out of the question to storm or besiege towns however

hostile, and the counsellors and creatures of the King urged him not

to risk the dangers of a journey to Rheims under such disadvantageous

circumstances.

Joan, wearied out by the endless procrastination and hesitation of the

King, left him, and preferred a free camp in the open fields to the

purlieus of the Court, with its feeble sovereign and plotting

courtiers. Joan of Arc on this occasion may be said to have 'sulked,'

but she showed her usual common sense in what she did, and her leaving

the Court seems to have given the vacillating King a momentary feeling

of shame and remorse. Orders were issued that the Court should be

moved on the 29th of June.

The royal army which started on that day for Rheims numbered twelve

thousand men; but this force was greatly increased on its march. By

the side of the King rode the Maid of Orleans; on the other side of

the King, Alençon. The Counts of Clermont, of Vendôme, and of

Boulogne—all princes of the blood—came next. Dunois, the Maréchal de

Boussac (Saint-Sevère), and Louis Admiral de Culan followed. And then,

in a crowd of knights and captains, rode the Seigneurs de Rais, de

Laval, de Loheac, de Chauvigny, La Hire, Xaintrailles, La Tremoïlle,

and many others.

Before the town of Auxerre a halt was called: it was still under the

influence of the English and Burgundians. A deputation waited upon

Charles, provisions were sent to the army, but the town was not

entered. Outside its fortifications the army rested three days, after

which it continued its march to Saint-Florentin, whose gates swung

open to the King; thence on to Brinon l'Archevêque, whence Charles

forwarded a messenger with a letter to his lieges at Rheims,

announcing his approach.

On the 4th of July the royal force had reached Saint-Fal, near Troyes.

Joan of Arc despatched a messenger summoning that place to open its

gates to the King; but Troyes was strongly garrisoned by a force of

half English half Burgundian soldiers, and these had sent for succour

to the English Regent, the Duke of Bedford. The army of the King

arrived before the gates of the town on the 4th of July; a sally was

made by the hostile garrison, but this was driven back. Pour-parlers

ensued. The King's heralds were informed by the garrison officers that

they had sworn to the Duke of Burgundy not to allow, without his

leave, any other troops to enter their gates. They went further, and

insulted the Maid of Orleans in gross terms, calling her a

'cocquarde'—whatever that ugly term may mean.

The situation was embarrassing. How could the town be taken without a

siege train and artillery? But to leave it in the rear, with its

strong garrison, would be madness. The King's men were in favour of

retiring and abandoning the expedition to Rheims. There happened to be

within the town of Troyes at this time a famous monk of the preaching

kind, named Father Richard. Father Richard had been a pilgrim, and had

visited the Holy Land, and had made himself notorious by interminable

sermons, for he was wont to preach half-a-dozen hours at a time.

Crowds had listened to him in Paris and other places. The English, who

probably thought his sermons insufferably long, or too much leavened

with French sympathies, drove him out of Paris, and he had taken

refuge at Troyes. The monk had heard much of Joan of Arc, and was

eager to see and speak with her, but his enthusiasm was mixed with a

religious and even superstitious fear in regard to the heroine. He was

allowed to enter the royal precincts, and approached the Maid of

Orleans with many a sign of the cross, and with sprinkling of holy

water. Seeing the good man's terror, Joan told him to approach her

without fear.

'Come forward boldly!' she said to the monk. 'I shall not fly away!'

And after convincing him that she was not a demon in any way, she made

him the bearer of a letter from her to the people in the town. The

negotiations between the army and the burghers lasted five days; the

town refusing to admit the King, and the King unwilling to pass the

town, but unable to take it by force. Charles was on the point of

giving up the attempt to reach Rheims when one of his Council pointed

out that as the expedition had been undertaken at the instigation of

Joan of Arc, it was only fair her judgment should now be followed, and

not that of any one else. Joan was summoned before the Council, when

she solemnly assured the King that in three days' time the place would

be taken.

'If we were sure of it,' said the Chancellor, 'we would wait here six

days.'

'Six days!' said the Maid. 'You will enter Troyes to-morrow.'

Mounting her horse, the Maid rode into the camp, and ordered all to

prepare to carry out a general assault on the next morning. Anything

that could be used in the shape of furniture and fagots, to make a

bridge across the town ditches, was collected. Joan, who had now her

tent moved up close to the moat, worked harder, says an eye-witness,

than any two of the most skilful captains in preparing the attack. She

directed that fascines should be thrown into the moat, across which

the troops were to pass to the town.

Early next day everything was in readiness for the attack, but at this

juncture, just as she was preparing to lead the storming party, the

Bishop of Troyes, John Laiguise, attended by a deputation of the

principal citizens, came from the town with offers of capitulation.

The people were ready to place themselves at the King's mercy, owing

probably to the terror the preparations made by Joan of Arc on the

previous evening had inspired them with, mixed, too, with the

superstitious dread they felt for her presence. Had not even the

English soldiers declared that, when attacked by the terrible Maiden,

they had seen what appeared to be flights of white butterflies

sparkling all around her form! How could these good people of Troyes

hope to withstand such a power? To add to this fear, it was remembered

by the citizens of Troyes that in it had been signed and concluded the

shameful treaty by which Charles VII. had been disinherited from his

crown and possessions. The people therefore gave in without further

struggle. The conditions of capitulation were soon arranged. The

burghers were granted the immunity of their persons and their goods,

and certain liberties for their commerce. All those traders who held

any office at the hands of the English government were to continue the

enjoyment of these offices or benefices, with the condition of taking

them up again at the hands of the King of France. No garrison would be

quartered upon the town, and the English and Burgundian soldiers were

to be allowed to depart with their goods.

The next day—the 10th of July—Charles and his host entered Troyes in

state, the Maid of Orleans riding by the side of the King, her banner

displayed as was her custom.

When, as had been arranged in the treaty of capitulation, the foreign

soldiers began to leave the place with bag and baggage (goods), Joan

was indignant at finding that some of these so-called goods were

nothing less than French prisoners. This was a thing that she could

not tolerate, treaty or no treaty; and, placing herself at the gate of

the town, she insisted that her imprisoned countrymen should be left

in her charge. The King naturally felt obliged to gratify her; so he

released the captives, and paid their ransom down. Before leaving

Troyes the next day, William Bellier, who had been Joan's host at

Chinon, was left as bailiff of the place, along with other officers.

Thence the army moved on by way of Châlons. Though still in the hands

of the English, a deputation of clergy and citizens met the King, and

placed themselves at his orders.

While in the neighbourhood of Châlons, Joan of Arc met some friends

who had arrived from Domremy; among them were two old village

companions, Gerardin d'Epinal and John Morel, to whom she gave her red

dress. In conversation with these she said that the only dread she had

in the future was treachery: a dread which seems to point in some

strange prophetic manner to the fate which was so soon to meet her at

Compiègne.

It was on the evening of the 16th of July that the royal host at

length came in sight of the massive towers of the great cathedral

church of Rheims. It was at Sept Saulx, about eight miles' distance

from Rheims, that the King waited for a deputation to reach him from

the town. Rheims was still filled with the English and Burgundian

adherents, and had Bedford chosen to throw, as he could well have

done, a force into that place, Charles might yet have been prevented

from entering its gates. Perhaps Bedford did not believe in the

possibility of Charles arriving at his goal, and had counted on the

King's well-known weakness and indecision, and on the hesitation of

such men as La Tremoïlle and others of his Council. The Regent had

received assurances from the officials in Rheims that they would not

admit Charles. But after what passed at Troyes and at Châlons, Charles

had not long to wait for a favourable answer from his lieges at

Rheims. Indeed, the deputation which met him at Sept Saulx were

effusive in their good offices and entreaties that the King should

forthwith enter his good city of Rheims.

The Archbishop (Regnault de Chartres), who had preceded the King by a

few hours to his town, came out to meet the King at the head of the

corporation and civic companies. From all sides flocked crowds eager

to welcome the King, and even more the Maid of Orleans. In those days

the people's cry of joy and triumph was 'Noël!'—but why that cry of

Christmas joy had become the popular hosanna, it is not easy to

conjecture.

Throughout that night the preparations for the coronation were

feverishly made both within and without the cathedral. On the 17th of

July, with all the pomp and ceremony that the church and army could

bestow, the King was crowned and anointed with the holy oil which four

of his principal officers had brought to the cathedral from the

ancient abbey church of Saint-Remy.

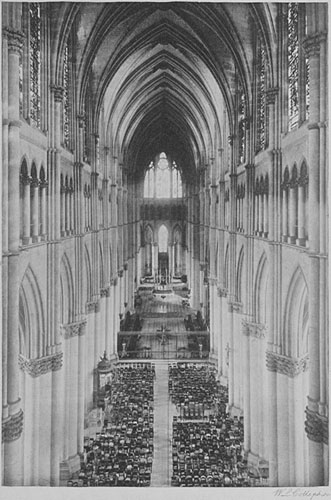

There exist few grander fanes in Christendom than the great cathedral

of Rheims. The thirteenth century, so prolific of splendid churches,

had expended all its wealth of lavish decoration on the gorgeous

portal, with its array of saints and sovereigns, under which passed

Charles VII. of France, with the Maid of Orleans on his right hand.

Hurried as had been the preparations for the ceremonial, the even then

ancient and venerable rites must have deeply impressed the spectators,

and the semi-sacred act was carried out with scrupulous care—the King

crowned and anointed with the holy oil, surrounded on his throne by

the ecclesiastical peers and high dignitaries of the Church, and

waited on by the secular peers during the crowning and after at the

coronation banquet.

At length was accomplished the darling wish of Joan of Arc's heart,

for now her King was regarded and sanctioned by all true French

persons as King of France, by the grace of God and Holy Church.

When the King received the crown from the hands of the Archbishop, a

peal of trumpets rang out, with such a mighty volume of sound that the

very roof of the cathedral seemed to shake again. Ingres, in his

striking picture of Joan of Arc, now in the gallery of the Louvre,

represents her standing by the high altar, clad in her white panoply

of shining steel, her banner held on high; below bows in prayer her

confessor, the priest Pasquerel, in his brown robes of the Order of

Augustin; and beyond stand her faithful squire and pages. The

heroine's face is raised, and on it sits a radiant look of mingled

gratitude and triumph. It is a noble idea of a sublime figure.

When the long-drawn-out ceremony came to an end, and after the people

had shouted themselves hoarse in crying 'Noël!' and 'Long live King

Charles!'—Joan, who had remained by the King throughout the day,

knelt at his feet and, according to one chronicle, said these words:

'Now is finished the pleasure of God, who willed that you should come

to Rheims and receive your crown, proving that you are truly the King,

and no other, to whom belongs this land of France.'

Many besides the King are said to have shed tears at that moment.

That seemed indeed the moment of Joan of Arc's triumph. The Nunc

Dimittis might well have then echoed from her lips; but in the midst

of all the rejoicing and festivity at this time Joan had saddened

thoughts and melancholy forebodings as to the future. While the

people shouted 'Noël!' as she rode through the jubilant streets by the

side of the King, she turned to the Archbishop, and said: 'When I die

I should wish to be buried here among these good and devout people.'

And on the prelate asking her how it was that at such a moment her

mind should set itself on the thought of death, and when she expected

her death to happen, she answered: 'I know not—it will come when God

pleases; but how I would that God would allow me to return to my home,

to my sister and my brothers! For how glad would they be to see me

back again. At any rate,' she added, 'I have done what my Saviour

commanded me to do.'

Her mission was indeed accomplished: that is to say, if her mission

consisted of the two great deeds which while at Chinon she had

repeatedly assured her listeners she was born to accomplish. These

were, first, to drive the English out of Orleans, and thereby deliver

that town; the second, to take the King to Rheims, where he would

receive his crown. The other enterprises, such as the wish to deliver

the Duke of Orleans from his captivity in England, and then to wage a

holy war against the Moslems, may be left out of the actual task

which, encouraged by her voices, Joan had set herself to accomplish.

But the two great deeds had now been carried out—and with what

marvellous rapidity! In spite of all the obstacles placed in her path,

not only by the enemies of her country, but by those nearest to the

ear of the King, Orleans had been delivered in four days' time, the

English host had been in a week driven out of their strongholds on the

Loire, and defeated in a pitched battle! The King unwillingly, and

with many of his Court opposed to the enterprise, after passing

through a country strongly occupied by the enemy without having lost a

man, had by the tact and courage of Joan of Arc been enabled to reach

Rheims; and after this successful march he had received his crown

among his peers and lieges, as though the country were again at peace,

and no English left on the soil of France. What was still more

surprising was, that all these things should have been accomplished at

the instigation and by the direction of a Maid who only a few months

before had been an unknown peasant in a small village of Lorraine. How

had she been able not only to learn the tactics of a campaign, the

rudiments of the art of war, but even the art itself? No one had shown

in these wars a keener eye for selecting the weakest place to attack,

or where artillery and culverin fire could be used with most effect,

or had been quicker to avail himself of these weapons. No one saw with

greater rapidity—(that rarest of military gifts)—when the decisive

moment had arrived for a sudden attack, or had a better judgment for

the right moment to head a charge and assault. How indeed must the

knights and commanders, bred to the use of arms since their boyhood,

have wondered how this daughter of the peasants had obtained the

knowledge which had placed her at their head, and enabled her to gain

successes and reap victories against the enemy, which until she came

none of them had any hope of obtaining. They indeed could not account

for it, except that in Joan of Arc was united not only the soul of

patriotism and a faith to move mountains, but the qualities of a great

captain as well. That, it seems to us, must have been the conclusion

that her comrades in arms arrived at regarding the Maid of Orleans.

Dunois stated that until the advent of the Maid the French had no

longer the courage to attack the English in the open field, but that

since she had inspired them with her courage they were ready to attack

any force of the army, however superior it might be. This testimony

was confirmed by Alençon also: he declared that in things outside the

province of warfare she was in every respect as simple as a young

girl; but in all that concerned the science of war she was thoroughly

skilled, from the management of a lance in rest to that of marshalling

an army; and that as regarded the use of artillery she was eminently

qualified. All the military commanders, he said, were amazed to see in

her as much skill as could be expected in a seasoned captain who had

profited by a training of from twenty to thirty years. 'But,' added

the Duke, 'it is principally in her use of artillery that she

displays her most complete talent.' And he proceeds to bear his high

tribute to her goodness of heart, which she displayed on every

possible occasion.

< INTERIOR - RHEIMS

INTERIOR - RHEIMS

Although her physical courage enabled her to face the greatest perils

and personal risks, she had a horror of bloodshed, and though her

spirit was 'full of haughty courage, not fearing death nor shrinking

distress, but resolute in most extremes,' she never entered battle but

bearing her banner in her hand; and to the last day of her appearance

on the field she strove with all her great moral force to induce the

rude and brutal men around her to become more humane even in the

hurly-burly of the din of battle. All unnecessary cruelty and

bloodshed made her suffer intensely, and we have seen how she

ministered to the English wounded who had fallen in fight. As far as

she could she prevented pillage, and she would only promise her

countrymen success on the condition that they should not prey upon the

citizens of the places they conquered. Even when she had passed the

day fasting on horseback, Joan would refuse any food unless it had

been honourably obtained. As a child she had been taught to be

charitable and to give to the needy, and she carried out these

Christian principles when at the head of armies; the 'quality of

mercy' with her was ever present. She distributed to the poor all she

had with her, and would say, with what truth God knows, 'I have been

sent for the consolation of the poor and the relief of the needy.' She

would take upon herself the charge of the wounded; indeed, she

may be considered as the precursor of all the noble hearts who in

modern warfare follow armies in order to alleviate and help the sick

and wounded. And she tended with equal care and sympathy the wounded

among the enemy, as well as those of her own side.

This is no invention, no fancy of romance, but the plain truth; for

there can be no disputing the testimony of those who followed Joan of

Arc and saw her acts.

Regarding herself, Joan of Arc said she was but a servant and an

instrument under Divine command. When people would avow that such

works as she had carried out had never been done in former times, she

would simply say: 'My Saviour has a book in which no one has ever

read, however learned a scholar he may be.'

In all things she was pure and saint-like, and her wonderful life, as

Michelet has truly said of it, was a living legend. Had she not been

inspired by her voices and her visions to take up arms for the

salvation of her country, Joan of Arc would probably have lived and

ended her obscure life in some place of holy retreat. An all-absorbing

love for all things sacred was her ruling idiosyncrasy. From her

childhood her delight was to hear the church bells, the music of

anthems, the sacred notes of the organ. Never did she miss attending

the Church festivals. When within hail of a church it was her wont,

however hurried the march, to enter, attended by any of the soldiers

whom she could induce to follow her, and kneel with them before the

altar. At the close of some stirring day passed in the midst of the

din of battle, and after being for hours in the saddle, she would, ere

she sought rest, always return thanks to her God and His saints for

their succour.

Joan also loved to mix in the crowd of poor citizens, and begged that

the little children should be brought to her. Pasquerel, her

confessor, was always told to remind Joan of Arc of the feast days on

which children were allowed to receive the Communion, in order that

she too might receive it with these innocents.

The army has probably ever been the home of high swearing: the

expression in French of 'ton de garnison' is an amiable way of

referring to that habit of speech; and we all know ancient warriors

whose conversation is thickly larded with oaths and profanity. This

habit Joan of Arc seems to have held in great abhorrence. We have seen

how she got La Hire to swear only by his stick; to another officer of

high rank, who had been making use of some strong oaths, she said:

'How can you thus blaspheme your Saviour and your God by so using His

name?' Let us hope her lesson bore fruit.

Throughout the land Joan of Arc was now regarded as the Saviour of

France. Nor at this time did the King prove ungrateful. In those days

nobility was highly regarded. It brought with it great prestige, and

much benefit accrued to the holders of titles. Charles now raised the

Maid of Orleans to the equal in rank of a Count, and bestowed upon

her an establishment and household. The grateful burghers of Orleans,

too, loaded her with gifts, all which honours Joan received with quiet

modesty. For herself she never asked anything. After the coronation at

Rheims, when the King begged her to make him a request, the only thing

she asked was, that the taxes might be taken off her native village.

Her father, who came to see her at Rheims, had the satisfaction of

carrying back this news to Domremy.

Although both King and nobles vied in paying honours to Joan of Arc,

it was from the common people, from the heart of the nation, that she

received what seems to have amounted to a feeling approaching

adoration. Wherever she passed she was followed by crowds eager to

kiss her feet and her hands, and who even threw themselves before her

horse's feet. Medals were struck and worn as charms, with her effigy

or coat-of-arms struck on them. Her name was introduced into the

prayers of the Church.

Joan, although touched by these marks of affection, never allowed the

people, as far as in her power lay, to ascribe unearthly influence to

her person. When in the course of her trial the accusation that the

people had made her an object of adoration was brought as a proof of

her heresy, she said: 'In truth I should not have been able to have

prevented that from being so, had God not protected me Himself from

such a danger.'

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUE TO NEXT CHAPTER

|

Please Consider Shopping With One of Our Supporters!

|

|

| |