Joan of Arc

Chapter 4

THE CAPTURE

We must now glance at the movements of the English since the

deliverance of Orleans and their defeat at Patay, and the French

King's coronation.

What proves the utter demoralisation of the English at this time is

that the Regent Bedford was not only afraid of remaining in Paris, but

had also taken refuge in the fortress of Vincennes. He was so poor

that he could not pay the members of Parliament sitting in Paris. Like

other bodies receiving no pay, the Parliament declined to work. So

restricted were all things then in Paris that when the child-king

(Henry VI.) was brought from London to be crowned there, not enough

parchment could be found on which to register the details of his

arrival.

For want of a victim to assuage his ire, the Regent disgraced Sir John

Fastolfe, whom he unknighted and ungartered, in order to punish him

for the defeat at Patay; and he wrote that the English reverses had

been caused by 'a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle,

that used fals enchantements and sorcerie.'

The Regent, whose degrading of Fastolfe and vituperation of Joan of

Arc did not serve to help, applied to his powerful brother-in-law, the

Duke of Burgundy, for aid. Burgundy came to the Regent's assistance,

bringing a small force with him from Picardy. Then Bedford bethought

him of his powerful relation in England, Henry Beaufort, the Bishop of

Winchester. Most opportunely for the Regent, the Bishop had collected

an army for the suppression of the Bohemian Hussites. The Regent

implored his uncle, the Bishop, to send this army for the defence of

the English and their interests, now in such dire jeopardy. Winchester

was a mean, avaricious prince, and his aid had to be bought. A treaty

was signed on the 1st of July, in which Winchester promised to bring

his troops to his nephew's assistance; but he delayed stirring till

the middle of that month. It pleased the crafty Bishop to know that

his great wealth made him all-powerful in England; for the English

Protector, the Duke of Gloucester, was a mere cipher compared to

Winchester; and now that his other nephew, the Protector of France,

was in distress, he could dictate his own terms to both. It was not

until the 25th of July that Winchester at length arrived with his army

in Paris. Then Bedford breathed more freely, and left the capital with

an army of observation to watch the movements of the French King.

It was now the earnest wish of Joan of Arc that Charles should march

direct on Paris, and perhaps had he done so he might have entered

that city with as little difficulty as he had entered Rheims; for if

once the King of France had appeared in person, many of the wealthy

citizens, as well as the majority of the common people, would have

welcomed him. Charles, however, as usual vacillated, and the precious

moment slipped by.

Philip (called 'the Good'), Duke of Burgundy, was at this time one of

the most powerful princes of Christendom. In addition to his titular

domain, he held the wealthy provinces of Burgundy, including Brabant,

Flanders, Franche-Comté, Holland, Namur, Lower Lorraine, Luxembourg,

Artois, Hainault, Zealand, Friesland, Malines, and Salines. This

much-territoried potentate was at the present juncture coquetting both

with Bedford and with Charles, playing one against the other. To the

former he promised an army, but only contributed a handful of men; to

the latter he made advances of friendship, as false as the man who

made them.

Joan had despatched two letters of a conciliatory tone to the Duke of

Burgundy from Rheims. The original of one of these is to be seen in

the archives at Lille. Like most of Joan of Arc's letters, it

commences with the name of Jesus and Mary. As Joan could not write,

the only portion of this letter which bears the mark of her hand is

the sign of the Cross placed at the left of those names at the top of

the document. She strongly urged the Duke in these letters to make

peace with the King; she appeals on the score of his relationship with

Charles, to his French blood, in order to prevent further bloodshed,

and to aid the rightful King. While waiting some definite answer from

the Duke, the King went to Vailly-sur-Aisne from Rheims. He arrived at

Soissons on the 28th of July, and Château Thierry on the next day.

Montmirail was reached on the 1st of August, Provins on the 2nd. It

will be seen that, instead of marching straight upon Paris, the King

was making a mere detour from Rheims towards the Loire.

It was soon evident that Charles and his civil councillors had no

intention of advancing direct upon Paris, and were merely marching and

counter-marching until they could, as they trusted, get the Duke of

Burgundy to join them.

In the meanwhile, Bedford saw his opportunity, and made prompt use of

it. Early in the month of August he issued a proclamation calling on

all the subjects of Henry of England in France and Normandy to rally

round their liege lord. Leaving Paris on the 25th of July, Bedford

marched to Melun with a force of ten thousand men. Melun was reached

on the 4th of August. On the day after Bedford's arrival at Melun a

letter was sent by Joan of Arc to her friends at Rheims, announcing

that the King's retreat on the Loire would not be continued by his

Majesty. The King had, in fact, met with a check to his advanced guard

at Bray-sur-Seine. Charles had, she informed her correspondents,

concluded a truce of fifteen days with the Duke of Burgundy, at the

expiration of which the Duke had promised to surrender Paris to the

King. But, she adds, it could not be certain whether the Duke would

keep to his promise. She concludes her letter by saying that should

the treaty not hold good, then the army of the King would be able to

take active measures.

This letter is vaguely dated from a lodging on the road to Paris. It

was, she knew, necessary to be near the capital at the close of the

period stipulated by Burgundy, and the royal army accordingly took the

northern road, leading to Paris.

On the 7th of August the royal force reached Coulommiers; on the 10th

La Ferté Milon, and on the 11th Crespy-en-Valois. Bedford, apprised of

this change in the movements of his foe, sent off an insulting letter

to Charles, whom he addressed as 'Charles who called himself Dauphin,

and now calls himself King!' The Regent reproaches the King for having

taken the crown of France, which he said belonged to the rightful King

of France and of England, King Henry; and he then styles the Maid of

Orleans 'an abandoned and ill-famed woman, draped in men's clothes and

leading a corrupt life.' He bids Charles to make either his peace with

him or to meet him face to face. Altogether a most rude, abusive, and

ungallant letter for one prince to send to another. This letter

reached Charles at Crespy-en-Valois on the 11th of August. Bedford was

then close at hand, and eager to provoke the King into attacking him.

Charles contented himself with pushing on his advanced guard as far as

Dammartin, remaining himself at Lagny-le-Sec.

During the 13th of August skirmishes took place between the advanced

guards of the armies, but without any result.

Bedford now returned to Paris—in order to collect more troops, some

said, others that he had found the French too strong to attack. The

towns and villages around Paris, hearing of these events, and that the

English had returned to the capital, showed now their readiness to

join the French cause.

On his way to Compiègne news reached the French King that Bedford had

left Paris and marched on Senlis. On the 15th of August the French

attacked the English at dawn. Their army, formed into companies, was

commanded by Alençon, René d'Anjou, the King, who had with him La

Tremoïlle, and Clermont. Joan of Arc was at the head of a detachment

with Dunois and La Hire. The English held a strong position, which

they had made still more so by throwing up palisades and digging

ditches.

What appeared destined to be a great engagement ended in a mere

skirmish. Neither Charles nor Bedford were eager to pit all on a

stake, and both preferred to play a waiting game. Charles retired on

Crecy, while Joan of Arc remained in the field. She had done all that

courage and audacity could to induce the English to attack. She had

ridden up to their palisades and struck them with the staff of her

banner. But nothing would make the English fight that day; and the

next, Joan had the mortification of watching the retreat of the

English upon Paris. Joan had nothing now left her to do but to rejoin

the King at Crecy.

On the 17th the King received the keys of the town of Compiègne, and

there he was welcomed on the next day with much loyalty. It was during

his stay at Compiègne that Charles heard the welcome news that the

people of Senlis had admitted the Count of Vendôme within their walls,

and had bestowed on him the governorship of their town. Beauvais had

also shown its loyalty, had made an ovation in honour of the King, and

had ordered the Te Deum to be sung, greatly to the annoyance of the

Bishop of that place—Peter Cauchon—a creature of the Anglo-Burgundian

faction, of whom we shall hear a good deal later on.

Charles remained at Compiègne until the expiration of the term during

which the treaty with the Duke of Burgundy relating to the disposal of

Paris remained open; but the negotiations ended in Burgundy contenting

himself with sending to Charles, John of Luxembourg and the Bishop of

Arras with words of peace. Arrangements were projected that in order

to come to a general peace the Duke of Savoy was to be called in as

mediator. In the meanwhile a truce was proposed, which was to last

until Christmas, with the proviso that the town of Compiègne should be

ceded to Burgundy during the continuance of the armistice. No allusion

appears to have been made regarding the fate of Paris.

Joan of Arc, knowing that without Paris all that she had fought for

and obtained would soon again be lost, resolved to see what she could

do without coming to the King for assistance. She bade Alençon be

ready to accompany her, as she wished, so she expressed it, to see

Paris at closer quarters than she had yet been able to do.

Joan of Arc left Compiègne accompanied by the Duke of Alençon on the

23rd of August, taking a strong force with them. At Senlis they

collected more troops; on the 26th they arrived at Saint Denis. Here

they were joined by the King, who may be supposed to have felt some

shame at not having started with them from Compiègne; he came very

unwillingly, it is said, for all that.

Bedford left Paris precipitately for Normandy, owing to the discovery

of a plot having been started to make over Rouen to the French. This

event must have opened the Regent's eyes to the uncertain tenure the

English held even in the old duchy of their kings. Bedford had left

Louis of Luxembourg in Paris to command its garrison of two thousand

English soldiers. De L'Isle Adam was in command of the Burgundian

soldiers. In addition to Luxembourg, who was a bishop (of Thérouanne)

as well as a soldier, Bedford had given charge of the joint command to

an English officer named Radley. The Bishop summoned the Parliament in

order that it should swear fealty to King Henry VI. The town walls and

ditches were carefully repaired and renewed. Guns were placed on the

towers, walls, and batteries; immense quantities of ammunition of iron

and stone were piled ready at hand, to be used for the defence of all

the gates and approaches of the city. The moats were deepened, and by

dint of threats and menace, and by frightening the people as to the

terrible revenge the French King would take on the town and its people

when it fell into his power, the citizens were cajoled into being made

the agents of their natural enemies, and in sheer terror helped to

strengthen the defences of their town.

During the first days of the siege only a few unimportant skirmishes

took place between besieged and besiegers. Joan of Arc was

indefatigable, and with her keen eye sought out the likeliest place

where an assault might be successfully carried; but she lacked troops

for storming such strong outworks as Paris then had. The capital was

not only defended by walls and towers, but the English held both the

upper and lower banks of the Seine.

From Saint Denis no assistance came from the King, and it was only on

the 8th of September that, having received reinforcements, Joan of Arc

was at length enabled to make a determined attack. It was a very high

and holy day in the Church Calendar—the Feast of the Virgin's

Nativity—and, not unmindful of the sacredness of that feast-day, Joan

of Arc had determined to make a general attack; for 'the better the

day the better the deed!' was her feeling on that anniversary. In

those times the western limit of Paris was where now the wide

thoroughfare of the Avenue de l'Opéra runs from north to south. The

walls of the city erected under Charles V., flanked by huge moats and

protected by double fortress towers, each tower having a double

drawbridge, made any attack almost a forlorn hope. The Regent's

departure from Paris points to the little fear he felt that Paris

could be taken by assault; and in this matter Bedford judged rightly.

Whether or not Joan felt that some Divine assistance would enable her

to surmount the barriers that lay between her and the town she was so

determined to win back for her King, we cannot say. She fought below

the walls with a courage which, if the others had equalled, might have

made Paris their own. The attacking force was divided into two

parts—one, commanded by Joan, Rais, and De Gaucourt, was to attack

the city at the Gate of Saint Honoré; the other, led by Alençon and

Clermont, was to cover the assailants, and prevent any sorties being

made by the garrison.

Joan's impetuous onslaught successfully carried the first barriers and

the boulevard in front of the gate; but here she met with a check—the

heavy gates were barred, nor could she prevail on the enemy to make a

sortie.

Joan of Arc, carrying her flag, dashed, under a heavy fire, into the

ditch, followed by a few of the most courageous of the soldiers. The

ditch was a deep but a dry one; and rising on the further side, close

beneath the town walls, was a second and a wider moat, full of water.

Here, unable to advance, but unwilling to retire, Joan of Arc and her

followers were exposed to a murderous hail of shot, arrows, and other

missiles. Sending for fagots and fascines to be cast into the moat, in

order to enable a kind of bridge to be thrown across, while probing

with the staff of her banner the depth of the water, Joan was struck

by a cross-bow bolt, which made a deep wound in her thigh. Refusing to

leave the spot, she urged on the soldiers to fill the ditch. The day

was waxing late, and the men, who had been fighting since noon, were

nearly exhausted. The news of Joan having been wounded caused a kind

of panic among the French. There came a lull in the fighting, and the

recall was sounded. Joan had almost to be forced back from before the

walls by the Duke of Alençon and other of the officers. Placed upon

her horse, she was led back to the camp, Joan protesting the whole

time that if the attack had only been continued it would have been

crowned with success. The spot where the heroine is supposed to have

been wounded is near where now stands Fremiet's spirited statue of the

Maid of Orleans, between the Rue Saint Honoré—named in later days

after the gate she had so gallantly attacked—and the Gardens of the

Tuileries.

Within the town a great fear had fallen on the citizens, divided as

they were between the hope of their countrymen forcing their way into

the city and fear as to how they would be treated by Charles should he

be victorious. Perhaps, had Joan of Arc's urgent entreaties of

continuing the attack been more vigorously responded to by the other

French commanders, she might have been in the end successful. At any

rate Joan herself was of that opinion.

The following day she was, in spite of the previous evening's failure

and her wound, as urgent as ever for further fighting; and again and

again implored Alençon to renew the attack. It seems the Duke was on

the point of complying, when there appeared on the scene René d'Anjou

and Clermont, sent by the King with the order for the Maid's immediate

return to Saint Denis. There was nothing to do but to obey, but it

must have been a bitter disappointment to the brave maiden when she

turned her back on Paris. Alençon did his best to encourage her in the

hope that it might yet fall. He gave orders for a bridge to be thrown

across the Seine at Saint Denis, in order to make a fresh attack on

the city from that quarter. However, on the next night this bridge was

ordered by Charles to be removed, and with its destruction fell any

hopes Joan might still have entertained of being able to take Paris.

All the blame of the want of success of the army before Paris was now

laid at the door of Joan of Arc; and the creatures of the Court, who

had long waited for an opportunity of this kind to show their bitter

jealousy of the heroine, now made no secret of their enmity. Foremost

of these was the Archbishop of Rheims, who now, in spite of Joan of

Arc's entreaties, was allowed by the King to make a truce with the

enemy. Another powerful foe was La Tremoïlle, who (as has been

pointed out by Captain Marin in his work on Joan of Arc) thought it to

be against his personal influence that the French should take Paris.

La Tremoïlle had shown, from Joan's first appearance at Court, his

entire want of confidence in her mission. He had unwillingly, after

the examination of the Maid by the doctors and lawyers at Poitiers,

conformed to the King's wish that a command should be given her in the

army. He had done all in his power to induce the King not to undertake

the expedition to Rheims. He had told the King, when nothing else

could be urged against the journey, that there was no money in the

royal coffers, and that consequently the soldiers would not receive

their pay. As it turned out, volunteers offered their services

gratuitously to escort Charles to his crowning. At Auxerre, La

Tremoïlle concluded a treaty with the citizens, which prevented Joan

from taking that town. At Troyes he tried to create a like impediment;

but here he was foiled, for Troyes capitulated. After the coronation,

he persuaded Charles not to go to Paris, but to go instead to linger

in his castle on the Loire; and thereby prevented what might then have

proved a successful attack on the capital. And he again succeeded in

thwarting the Maid of Orleans when he resisted her wish to make a

second attack upon Paris. Later on it was La Tremoïlle who tried to

make Joan of Arc fail at the siege of Saint Pierre-le-Moutier. When

she was unsuccessful before La Charité-sur-Loire, and when the blame

of that failure was laid at Joan's door, La Tremoïlle for very

shame was obliged publicly to acknowledge the heroic zeal with which

she had carried out the operations of that siege. The higher Joan's

popularity rose among the people and in the army, the more her two

bitter enemies, La Tremoïlle and the Archbishop of Rheims, shared

between them their jealous dislike.

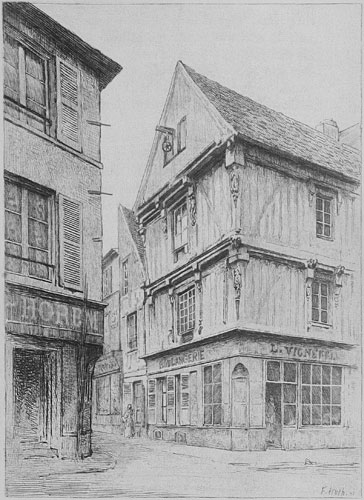

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY HOUSES - COMPIÈGNE

FIFTEENTH-CENTURY HOUSES - COMPIÈGNE

Thus, even before her capture and trial, Joan of Arc met with some of

her worst foes among those whose duty it was to have been her

staunchest friends and helpers; and, deplorable to say, among her own

countrymen.

Charles left Saint Denis on the 13th of September. Before his

departure, Joan of Arc performed an act which indicated that she felt

her mission to be finished. In the old fane of Saint Denis, the

tomb-house of the long line of French kings, she solemnly placed her

armour and arms at the foot of an image of the Holy Mother, near the

spot where were kept the relics of the Patron Saint of France. By that

act of humility she seemed to wish to show her abnegation of any

further earthly victory by the aid of arms.

We have now arrived at the turning-point of Joan of Arc's successes,

and although the heroine is even more admirable in her days of

misfortune and suffering than in those of her triumphs, when she led

her followers on from victory to victory, the course of her brief life

now darkens rapidly, and the approaching fate of the brave-hearted

maiden is so terrible that it requires some courage to follow her to

the very end, glorious as that end was, and bright with its sainted

heroism.

The King's return journey from Compiègne to Gien was so hurried that

it almost resembled a flight. Avoiding the towns still doubtful in

their loyalty to him, Charles sped from Lagny to Bovins, then to Bray,

Courtenay, Château-Regnaut, and Montargis, arriving at Gien on the

21st of September. Ere this time there could be little doubt of the

Duke of Burgundy's unwillingness to abide by his pledge, and restore

Paris to Charles. The Duke and Bedford had in fact already come to

terms. The Regent resigned to Burgundy the Lieutenancy of the country,

keeping only the now empty title of Regent and the charge of Normandy.

The result of the King's withdrawal from the neighbourhood of Paris,

and his hurried march, or rather retreat, to Gien, was that the

English felt that there was now no longer any fear of their being

drawn out of the capital. They promptly marched on and occupied Saint

Denis, pillaging that town and carrying off as a trophy the arms which

Joan of Arc had placed by the shrine of Saint Denis, in the ancient

basilica of Dagobert.

The other towns, which had so recently returned to their allegiance to

Charles, were again abandoned to the English, who punished them by

levying large ransoms on the citizens. The surrounding country was

laid waste, and Joan of Arc had the mortification of seeing that,

without any attempt being made to defend her people, the places which

had so shortly before been the scene of her triumphs were now allowed

to be reoccupied by the English and their allies. Normandy, Picardy,

and Burgundy were once more in possession of the enemy.

At length Joan obtained Charles' permission to attack La Charité,

where the enemy were in force, and from whence they threatened the

French forts on the Loire. At Bourges she assembled a few troops, and

in company with the Sire d'Albret she laid siege to Saint

Pierre-le-Moutier. Then, although feebly supported, Joan led the first

column of attack. This attacking column might have been called a

forlorn hope, so few men had she with her. The little party were

repulsed, and at one moment her squire, d'Aulon, saw that his brave

mistress was fighting alone, surrounded by the English. At great peril

she was rescued from the mêlée. Asked how she could hope to succeed in

taking the place with hardly any support, she answered, while she

raised her helmet, 'There are fifty thousand of my host around me,'

alluding to the vision of angels that in moments of extreme peril she

relied on. D'Aulon in vain urged her to beat a retreat, and retire to

a place of safety; she insisted on renewing the attack, and gave

orders for crossing the moat on logs and fascines. A roughly

constructed bridge over the fosse was then made, and after a desperate

struggle the fortress was taken.

This occurred early in the month of November (1429). A few years ago a

stained-glass window commemorative of the Maid of Orleans having saved

the church in Saint Pierre-le-Moutier (it had been converted by the

besieged into a warehouse for the goods and chattels of the citizens)

was placed in the building she had preserved from destruction.

The next siege undertaken by Joan of Arc was that of La Charité—a far

larger and more strongly garrisoned town than the other. La Charité was

held by one Peter Grasset, who had been its governor for seven years.

It was not only strongly defended by fortifications, but fully

victualled for a prolonged siege. Joan and her little army had not the

material necessary for carrying on such a siege as that of La Charité

would require—the very sinews of war were wanting. Charles would not

or could not contribute a single écu d'or, and Joan had to solicit help

and funds from the towns. In the public library at Riom is preserved

the original letter addressed by the Maid of Orleans to 'My dear and

good friends the clergy, burghers, and citizens of the town of Riom.'

It was sent to that place on the 9th of November from Moulins. In this

letter, the only one to which is affixed the Maid's signature, spelt

'Jehonne,' possibly signed by herself, she says that her friends at

Riom are aware of how the town of Saint Pierre-le-Moutier had been

taken, and she adds that she has the intention of driving out (de

faire vider) the other towns hostile to King Charles. She begs the

citizens of Riom, in order to accomplish this, to provide her with the

means of pushing forward the siege of La Charité, and asks them to

supply her with powder, saltpetre, sulphur, bows and arrows,

cross-bows, and other material of war, having exhausted all her stock

of such things in the late siege. Whether or not the burghers of Riom

were able to carry out Joan's wishes is not known. The town of Bourges,

however, provided funds out of its customs, and Orleans also sent

soldiers and artillerymen ('joueurs de coulverines') to the Maid's

army for the siege of La Charité.

But in spite of all efforts Joan of Arc was destined to fail in this

undertaking. No doubt her enemies at Court helped to thwart all her

attempts at raising a sufficient force to beleaguer so strong a place

of arms, and seeing her hopes of taking La Charité by assault vanish,

Joan of Arc relinquished the undertaking.

The remainder of that winter Joan of Arc passed in what must have

tried her high spirit sorely—inaction.

Accompanying the Court, she went from Bourges to Sully-sur-Loire, and

revisited Orleans. In the latter town we find some traces of her

passage, and some further traits of her sweet nature, and of that

simplicity which had endeared her so deeply to the hearts of the

people: a disposition no success altered, no disappointment

embittered. What was the chief charm of her character was this

simplicity, >her entire freedom from self-glorification, her horror of

it being imagined that she was a supernatural or miraculous being,

even when those supernatural and miraculous powers were considered as

coming direct to her from Heaven—in fact, to use a slang but

expressive phrase, her utter freedom from humbug. This is one of the

most marked features of her character, although not the most glorious

or salient to those who are dazzled by her triumphs and extraordinary

career.

When she was told by people that they could well understand how little

she feared being in action and under fire, knowing that she had a

charmed life, she answered them that she had no more assurance of not

being killed than the commonest of her soldiers; and when some foolish

creatures brought her their rosaries and beads to touch, she told them

to touch these themselves, and that their rosaries would benefit quite

as much as if she had done so.

On one occasion at Lagny she was asked to resuscitate a dead child.

One of the greatest of the French nobles wrote to ask her which of the

rival Popes was the true one. When asked on the eve of a battle who

would be victor, she answered that she could no more tell than any of

the soldiers could. A woman named Catherine de la Rochelle, who

assumed the power of knowing where money was hidden, was commanded by

the King to take Joan of Arc into her confidence. The latter soon

discovered that Catherine was a fraud, and refused >to have anything

to do with her. Catherine had suggested going to the Duke of Burgundy

to arrange a peace between him and the French King, to which

proposition Joan of Arc very sensibly said that it seemed to her that

no peace could be made between them but at the lance's point. Joan had

seen too much of the duplicity of the Duke to believe in any of his

treaties and promises.

The early months of the year 1430 were months of anxiety for the

citizens of Orleans and the other towns which had thrown off the

English allegiance. The truce made between Burgundy and France expired

at Christmas of the former year, but was renewed till Easter. Early in

the year, the burghers of Rheims implored help of Joan of Arc, and not

of the King, thus proving how far greater trust was placed in the

hands of the Maid of Orleans, by such a town as Rheims, than in the

goodwill of the King.

Twice during the month of March did Joan have letters written to

reassure them of aid in case of need. 'Know,' she says in a letter

dated the 16th of March, 'that if I can prevent it you will not be

assailed; and if I cannot come to your rescue, close your gates, and I

will make them [the English] buckle on their spurs in such a hurry

that they will not be able to use them.'

In the second letter to the people of Rheims, written at Sully on the

28th of March, Joan tells them that they will soon hear some good

news about herself. This good news referred no doubt to her return to

the field, for we find that by the end of that month she was again on

the march.

It was early in the month of April, 1430, that Joan of Arc left the

Court and rode to the north, on what was to prove her last expedition.

It is said that while at Melun, during Easter week, she was told by

her voices that she would be taken prisoner before St. John's Day.

It was at Lagny that an incident occurred which formed one of the

accusations brought against the Maid by her judges, and to which

reference may now be made. A freebooter, named Franquet d'Arras, had,

at the head of a band of about three hundred English freelances, held

all the country-side in terror round about Lagny. Hearing of this,

being in the neighbourhood of Lagny, Joan of Arc gave orders that

Franquet and his band should be attacked. The French were in number

about equal to the English. After a stubborn fight, the English were

all killed or captured. Among the latter was the chief of the robbers,

Franquet d'Arras. It was proved before the bailiff and justices of

Lagny that Franquet had not only been a thief, but a murderer, and he

was consequently condemned to die. Joan of Arc wished that he should

be exchanged for a French prisoner, but this French prisoner had

meanwhile died. The justices of Lagny insisted on having their

sentence carried out, to which Joan at length unwillingly gave way,

and Franquet met with his deserts. We cannot see how the Maid was to

blame in this affair; but this thing was one of the accusations which

helped to bring her to the stake.

On the 17th of April the truce agreed to between King Charles and

Burgundy came to an end. At this time the town of greatest strategical

importance to Burgundy was that of Compiègne. Holding Compiègne, the

Duke of Burgundy held the key of France. King Charles, with his

habitual carelessness, had been on the point of handing over Compiègne

to the Duke as a pledge of peace; and no doubt he would have done so

had not the inhabitants protested. Charles then surrendered the town

of Pont Sainte-Maxence to Burgundy instead of Compiègne. But this sop

did not at all satisfy the greedy Duke, whose mouth watered for

Compiègne, which he was determined to obtain by fair or by foul means.

At Soissons the Duke had succeeded in gaining the Governor by a bribe,

and had, through this bribe, obtained the place; and there is little

reason not to suppose that he was still more ready to offer a still

greater bribe to obtain Compiègne. The Governor of Compiègne, William

de Flavigny—a man very deeply suspected, writes Michelet of him—was

not likely to refuse a bribe; and, as we shall see, he acted in a

manner that has made the accusation of his treachery to his country

and Joan of Arc almost a certainty.

It was to prevent, if possible, Compiègne falling into the hands of

Burgundy that Joan of Arc hastened to its defence. On the 13th of May

she reached Compiègne, where she was received with great joy by the

citizens. The Maid lodged in the town with Mary le Boucher, wife of

the Procureur of the King. At Compiègne were some important Court

officials—the Chancellor Regnault de Chartres, no friend to Joan as

we have seen, Vendôme, and others. The country around and the places

of armed strength were all in the occupation of the English and

Burgundians; near Noyon, the town of Pont-l'Evêque was in the

possession of the English. This place Joan of Arc attacked, and she

was on the point of capturing it when a strong force of Burgundians

arrived from Noyon, and Joan had to beat a retreat on Crecy. On the

23rd of May, news reached Joan that Compiègne was threatened by the

united English and Burgundian forces, under the command of the Duke

and the Earl of Arundel. By midnight of that day, Joan of Arc was back

again in Compiègne. She had been warned of the danger of passing, to

gain the town, through the enemies' lines with so small a company.

'Never fear!' she answered, 'we are enough. I must go and see my good

friends at Compiègne.'

These words have been appropriately placed on the pedestal of the

statue of the heroine in front of the Hôtel de Ville in Compiègne.

By sunrise all her troopers were within the town: not a man was

missing.

Compiègne was a strongly fortified place, resting on the left bank of

the river Oise, across which, as at Orleans, one long stoutly defended

bridge connected the right bank with the town. In front of the bridge

was one of those redoubts which were in those days called

'boulevards.' This boulevard was surrounded by a wet moat or ditch

connected with the principal bridge by a drawbridge, closed or opened

from within at pleasure. The town was surrounded and protected by a

broad and deep moat, filled from the river. Behind this moat rose the

town walls, girt with strong towers at short intervals. On the right

bank of the river extended a wide stretch of fertile meadow land,

bounded on the northern horizon by the soft low-lying hills of

Picardy. From the circuit of the walls across the plain the eye rested

on the towns of Margny, of Clairvoix, and of Venette. The Burgundians

were encamped at Margny and at Clairvoix; the English, under the

command of Montgomery, were encamped at Venette.

The evening of the day on which she had arrived at Compiègne (the 24th

of May), Joan of Arc resolved to attack the Burgundians, both at

Margny and also at Clairvoix. Her plan was to draw out the Duke of

Burgundy, should he come to the support of his men at these places. As

to the English at Venette, she trusted that Flavy with his troops at

Compiègne would prevent them from cutting her off after her attack on

the Burgundians, and so intercepting her return to the town; but this

unfortunately was the very disaster which occurred.

In front of the bridge the redoubts were filled by French archers to

keep off any attack made by the English, and Flavy had placed a large

number of boats filled with armed men, principally bowmen, in

readiness along the river to receive their companions should they meet

with a repulse in their attack on the Burgundians.

It was about five o'clock that afternoon when Joan of Arc rode out of

Compiègne at the head of five hundred horsemen and foot soldiers.

Flavy remained within the town, of which he was Governor. The attack

led by the Maid on Margny, with splendid impetuosity, proved a

complete success, and the enemy fled for shelter to their companions

at Clairvoix. Here the resistance made was far more stubborn. While

the French and Burgundians were combating in the meadows at Clairvoix,

the English came from Venette to the assistance of their allies, and

attacked the French in their rear. A panic was created by this attack

among the French troops, and a sauve qui peut ensued, both foot and

horse dashing back in confusion towards Compiègne, and when they

reached the river either taking refuge in the boats or on the redoubts

near the bridge. Mixed among this panic-stricken crowd of fugitives

came the English in hot pursuit, followed by the Burgundians.

Carried away by the throng of frightened soldiers, Joan was among the

last to leave the field, and to those who cried to her to make her

escape she answered that all might yet be saved, and urged her men to

rally. Nevertheless, she was forced back towards the bridge, across

which fugitives were making their escape into the town. In a few

seconds Joan could have been safe across the drawbridge, and under

shelter of the towers which defended it. At this instant, whether

intentionally to exclude the heroine from safety, or through panic and

fear of the Burgundians and English entering the town along with the

French, the drawbridge was lifted, and Joan, with a handful of the

faithful few who were ever at her side in time of peril, was

surrounded by a sea of foemen. In a moment half a dozen soldiers

secured her horse and seized her on every side, trying to drag her out

of the saddle. The long skirts which the heroine wore were soon torn

off by these rough hands. An archer of Picardy, belonging to the army

of John of Luxembourg, wrenched her from her horse and made her

prisoner. Her brother Peter, her faithful squire d'Aulon, and Pothon

de Xaintrailles were all captured at the same time.

Thus fell Joan of Arc into the hands of her enemies, and the question

whether through treachery or not has never been settled.

According to an old work published early in the sixteenth century,

called Le Miroir des Femmes Vertueuses, Joan of Arc had taken the

communion in the Church of Saint James at Compiègne, and was standing

leaning against a pillar of that church; a large number of citizens

with many children stood around, to whom she said: 'My children and

dear friends, I bid you to mark that I have been sold and betrayed,

and that I shall be shortly put to death. So I beseech you all to pray

to God for me, for never more shall I be able to be of service to the

King or to the kingdom of France.'

This story, which, whether authentic or not, is surely a touching one,

is full of the spirit of the heroine. It rests upon the testimony of

two persons, one eighty-six and the other eighty-eight years of age,

by whom the author was told the tale in 1498, both affirming that they

had been in the church when Joan of Arc spoke of her betrayal. There

can be but little doubt that Joan had had for some time before she

went to Compiègne a presentiment of her soon falling into her enemies'

power. On the eve of the King's coronation at Rheims she said to her

friends that what she alone feared was treason—a foreboding too soon,

alas! to come true. She never, however, seems to have fixed on any

particular period when the treason she dreaded would occur; and during

her trial she acknowledged that, had she known she would have been

taken prisoner during the sortie on the 24th of May, she would not

have undertaken that adventure.

One of her best historians, M. Wallon, thinks that the words which she

is supposed to have spoken to the people in the Church of Saint James

at Compiègne were owing to her discouragement at not having, a few

weeks previously, been able to cross the river Aisne at Soissons, and

thus finding herself prevented from attacking the Duke of Burgundy at

Choisy, and thence having been obliged to return to Compiègne. Wallon

points out that in coming to defend Compiègne, Joan of Arc came

entirely at her own instigation, and that during the previous six

months Flavy had defended Compiègne against the English and

Burgundians with success and energy; nay more, that, in spite of

bribes from the Duke of Burgundy, Flavy contrived to hold the town

till the close of the war.

On the other side, a recent writer of the heroine's life, especially

as regarded from a military standpoint, M. Marin, gives at great

length his reasons for believing in the treachery of Flavy. M. Marin

points out that, in the first place, Flavy's character was a

notoriously bad one; secondly, that he was very possibly under the

influence of both La Tremoïlle and the Chancellor Regnault de

Chartres, bitter opponents, as we have already shown, of the Maid;

thirdly, that it was in Flavy's interest that the prestige of saving

Compiègne from the Burgundians and English should be entirely owing to

his own conduct; and fourthly, that he, Flavy, with the majority of

the French officers, was affected against Joan of Arc since the

execution of Franquet d'Arras. M. Marin goes on to prove that Joan of

Arc might have been rescued without difficulty, and that the enemy

could not have forced their way into the town alongside of the

retreating French, unless they were ready to be cut up as soon as they

had come within its walls. M. Marin's opinion, having the authority of

a soldier, carries weight with it; and his opinion is that Joan of Arc

was deliberately betrayed by Flavy, and purposely allowed to fall into

the hands of her enemies.

The names of La Tremoïlle and Regnault de Chartres should also be

pilloried by the side of that of Flavy—the two great courtiers who

held the ear of the King, and who had always plotted against Joan of

Arc. As has already been said, it was Regnault de Chartres who had the

effrontery to announce the news of Joan of Arc's capture to the

citizens of Rheims as being a judgment of Heaven upon her. She had,

this mean prelate said, offended God by her pride, and in wearing rich

apparel, and in having preferred to follow her own will rather than

that of God! Verily, and with reason, might poor Joan have prayed to

be delivered from such friends as those creatures and courtiers about

her King, for whom she had done and suffered so much.

The archer who had captured Joan of Arc was in the pay of the Bastard

of Wandome, or Wandoune, and this Wandome was himself in the service

of John de Ligny, a vassal of the Duke of Burgundy, and a cadet of

the princely house of Luxembourg. Like most younger sons, John de

Ligny was badly off, and the temptation of the English reward in

exchange for his prisoner, whose escape he greatly feared, overtopped

any scruples he may have felt in receiving this blood-money.

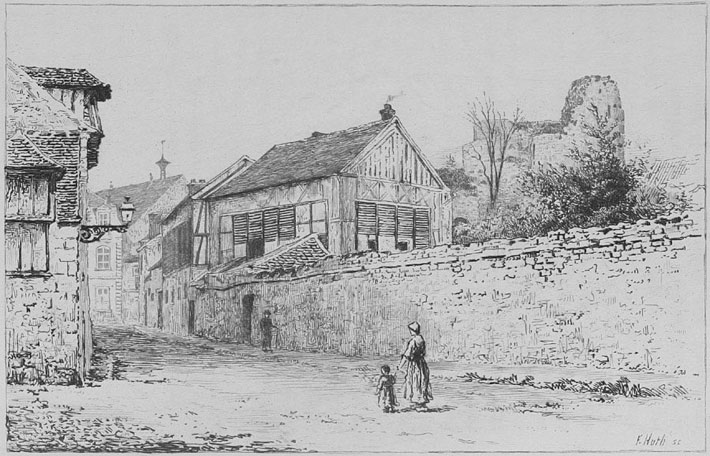

TOUR DE LA PUCELLE - COMPIÈGNE

TOUR DE LA PUCELLE - COMPIÈGNE

The historian Monstrelet tells us he was present when Joan of Arc was

brought into the Burgundian camp, at Margny, and before the Duke of

Burgundy. But the old chronicler relates nothing with regard to that

eventful meeting; only he is eloquent on the joy caused by the capture

of the Maid of Orleans among the English and their allies; and he

tells us that in their opinion Joan's capture was equal by itself to

that of five hundred ordinary prisoners, for they had feared her, he

adds, more than all the other French leaders put together. Of the high

opinion held by her enemies of the Maid's influence, one could not ask

for a more remarkable proof than this testimony, coming as it does

from a partisan of her foes.

After three days passed at Margny, Joan of Arc was taken, for greater

security, by Luxembourg to the castle of Beaulieu, in Picardy.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUE TO NEXT CHAPTER

|

Please Consider Shopping With One of Our Supporters!

|

|

| |